I first met Signavio CEO Gero Decker in 2008, when he was a researcher at Hasso Platner Institut and emailed me about promoting their BPMN poster — a push to have BPMN (then version 1.1) recognized as a standard for process modeling. I attended the academic BPM conference in Milan that year but Gero wasn’t able to attend, although his name was on a couple of that year’s modeling-related demo sessions and papers related to Oryx, an open source process modeling project. By the 2009 conference in Ulm we finally met face-to-face, where he told me about what he was working on, process modeling ideas that would eventually evolve into Signavio. By the 2010 BPM conference in Hoboken, he was showing me a Signavio demo, and we ended up running into each other at many other BPM events over the years, as well as having many online briefings as they released new products. The years of hard work that he and his team have put into Signavio have paid off this week with the announcement of Signavio’s impending acquisition by SAP (Signavio press release, SAP press release). There have been rumors floating around for a couple of days, and this morning I had the chance for a quick chat with Gero in advance of the official announcement.

The combination of business process intelligence from SAP and Signavio creates a leading end-to-end business process transformation suite to help our customers achieve the requirements needed to gain a competitive edge.

Luka Mucic, CFO of SAP

SAP is launching RISE with SAP today, with the Signavio acquisition a part of the announcement. RISE with SAP is billed as “business transformation as a service”, providing business process redesign (including Signavio), technical migration (which appears to be a push to get reluctant customers onto their current platform), and building an intelligent enterprise (which is mostly a cloud infrastructure message).

This is a full company acquisition, including all Signavio employees (numbering about 500). Gero and the only other co-founder still at Signavio, CTO Willi Tscheschner, will continue in their roles to drive forward the product vision and implementation, becoming part of SAP’s relatively new Business Process Intelligence unit, which is directly under the executive board. Since that unit previously contained about 100 people, the Signavio acquisition will swell those ranks considerably, and Gero will co-lead the unit with the existing GM, Rouven Morato. A long-time SAP employee, Morato can no doubt help navigate the sometimes murky organizational waters that might otherwise trip up a newcomer. Morato was also a significant force in SAP’s own internal transformation through analytics and process intelligence, moving them from the dinosaur of old to a (relatively) more nimble and responsive company, hence understands the importance of products like Signavio’s in transforming large organizations.

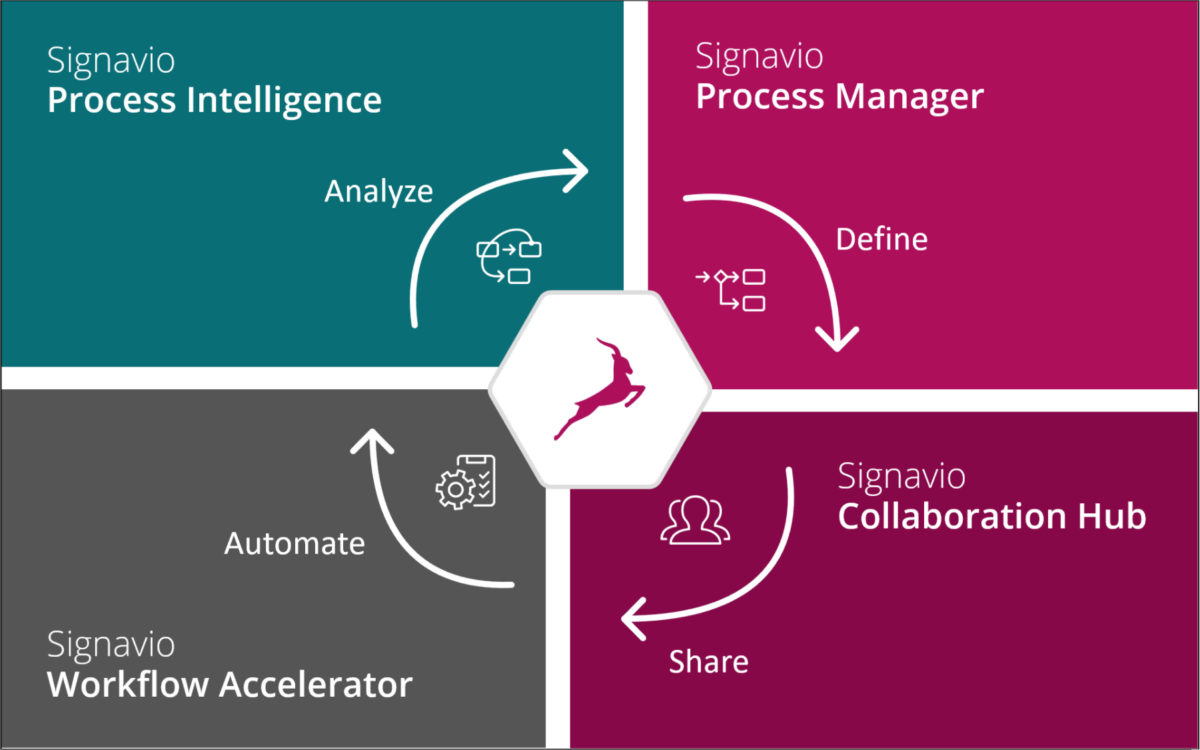

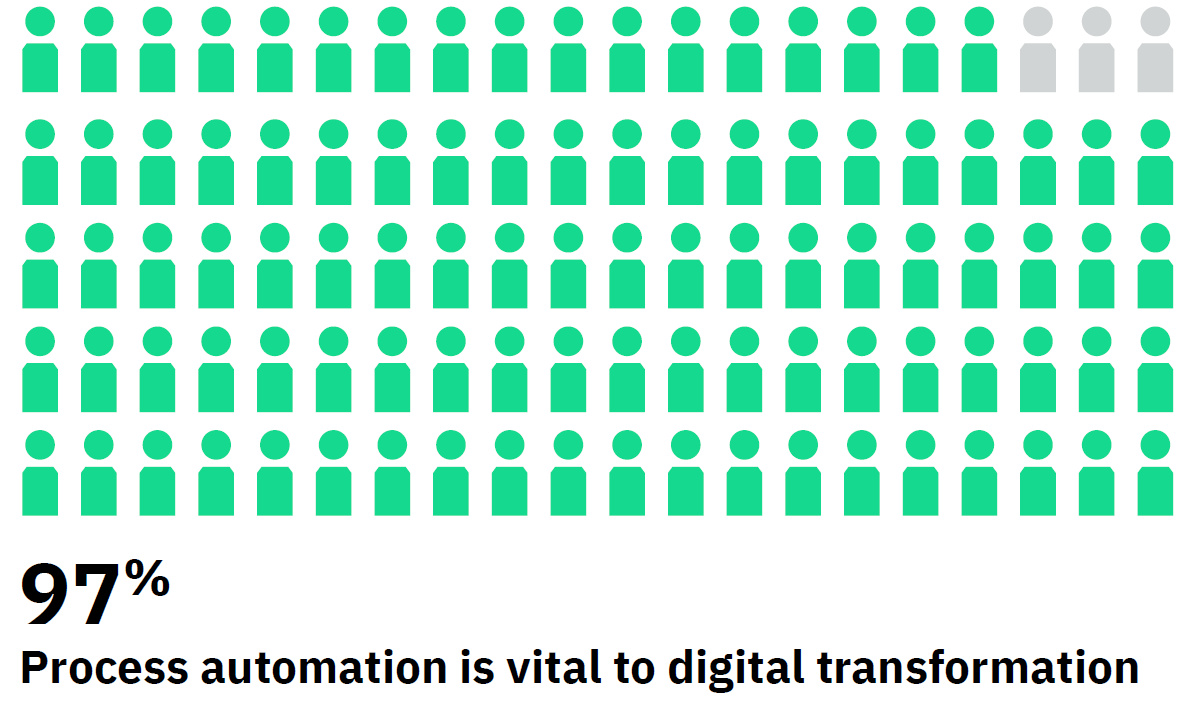

Existing Signavio customers probably won’t see much difference right now. Over time, capabilities from SAP will become integrated into the process intelligence suite, such as deeper integration to introspect and analyze SAP S/4 processes. Eventually product names and SKUs will change, but as long as Gero is involved, you can expect the same laser focus on linking customer experience and actions back to processes. The potential customer base for Signavio will broaden considerably, especially as they start to offer dashboards that collect information on processes that include, but are not limited to, the SAP suite. In the past, SAP has been very focused on providing “best practice” processes within their suite; however, if there’s anything that this past year of pandemic-driven disruption has taught us, those best practices aren’t always best for every organization, and processes always include things outside of SAP. Having a broader view of end-to-end processes will help organizations in their digital transformations.

Obviously, this is going to have an impact on SAP’s current partnership with Celonis, since the SAP Process Mining by Celonis would be directly in competition with Signavio’s Process Intelligence. Of course, Signavio also has a long history with SAP, but their partnership has not been as tightly branded as the Celonis arrangement. Until now. Celonis arguably has a stronger process mining product than Signavio, especially with their launch into task mining, and have a long history of working with SAP customers on their process improvement. There’s always room for partners that provide different functionality even if somewhat in competition with an internal functionality, but Celonis will need to build a strong case for why a SAP customer should pick them over the Signavio-based, SAP-branded process intelligence offering.

Keep in mind that SAP hasn’t had a great track record of process products that aren’t part of their core suite: remember SAP NetWeaver BPM? Yeah, I didn’t think so. However, Signavio’s products are focused on modeling and analyzing processes, not automating them, so they might have a better chance of being positioned as discovering improvements to processes that are automated in the core suite, as well as giving SAP more visibility into how their customers’ businesses run outside of the SAP suite. There’s definitely great potential here, but also the risk of just becoming buried within SAP — time will tell.

Disclosure: Signavio has been a client of mine within the last year for creating a series of webinars. I was not compensated in any way for writing this post (or anything else on this blog, for that matter), and it represents my own opinions.