I feel like I’m barely back from the academic research BPM conference in Utrecht, and I’m already at Camunda’s annual CamundaCon, being held in New York (Brooklyn, actually) — the first time for the main conference outside of Germany. The location change from Berlin is a bit of a tough call since they will lose some of the European customers who don’t have a budget for international travel, but the opportunity to see their North American customers will make up for it. They’re also running the conference virtually for those of you who can’t be here in person, and you can sign up for free to attend the presentations online.

Although I don’t blog about anything that happens after the bar is open, I did have a couple of interesting conversations at the networking event last night about my relationship with Camunda. I’m here this week as an independent analyst, and although they are covering my travel expenses, I’m not being paid for my time and (as usual) the opinions that I write here are my own. This is the same arrangement I have with any vendor whose conference I attend, although I have got a bit pickier about which locations I’m willing to travel to (hint: not Vegas). I’ve been covering Camunda a long time, starting 10 years ago with their fork from Activiti, back when they didn’t capitalize their name. They’ve been a client of mine in the past for creating white papers, webinars and speaking at their conference. I’ve also worked with some of their clients on technical strategy and architecture, which is the other side of my business.

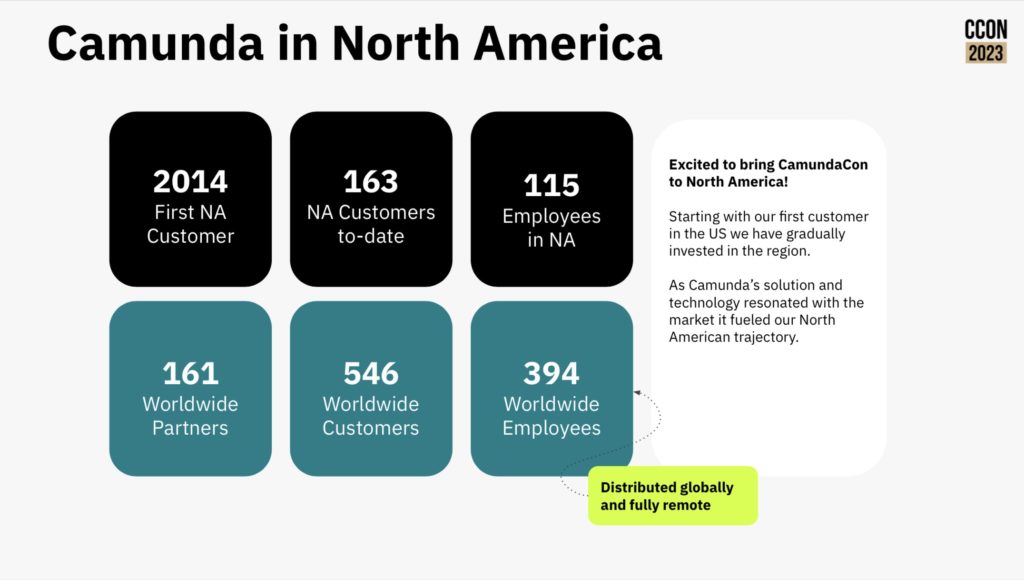

The first day opened with a keynote from Camunda CEO Jakob Freund giving a brief retrospective of the last 10 years of their growth and especially their current presence in North America. There’s over 200 people attending today in person at the 74Wythe event space, plus an online contingent of attendees. He started with a vision of the automated enterprise, and how this is made difficult by the complexity of mission-critical processes that cross multiple silos of systems and organizational departments. Process orchestration allows for automation of the end-to-end processes by acting a a controller that can invoke the right resource — whether a person or a system — at the right time while maintaining end-to-end visibility and management. If you’re not embracing process orchestration, you run the risk of having broken processes that have a significant impact on your customer satisfaction, efficiency and innovation.

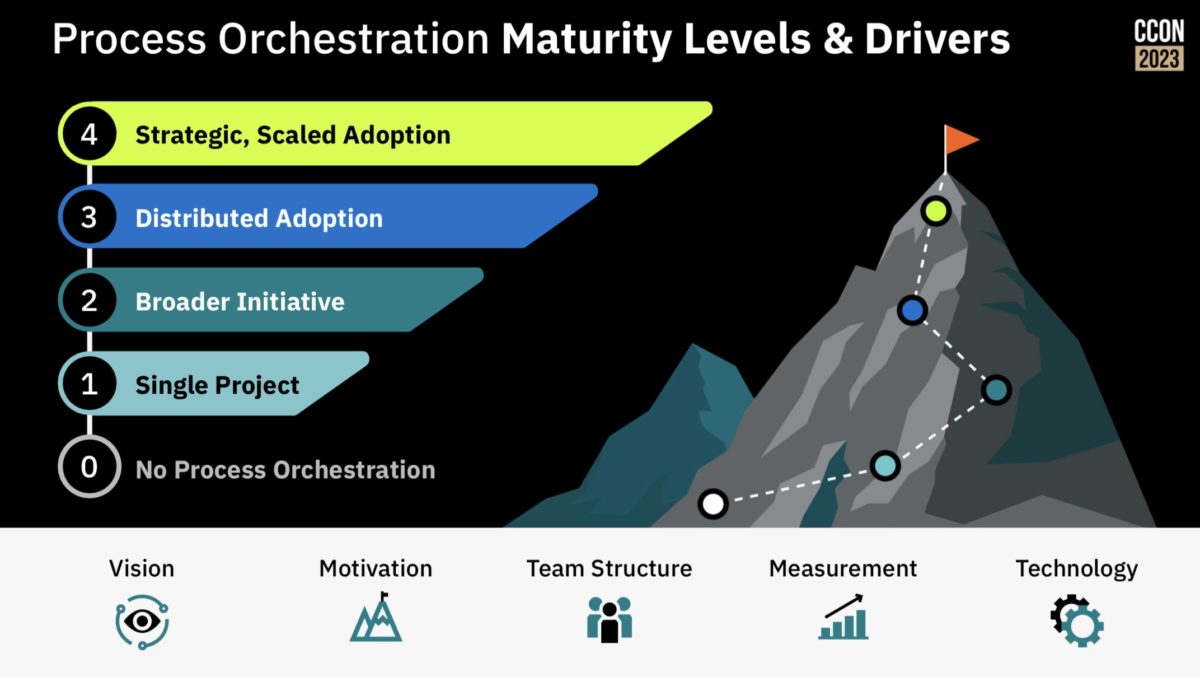

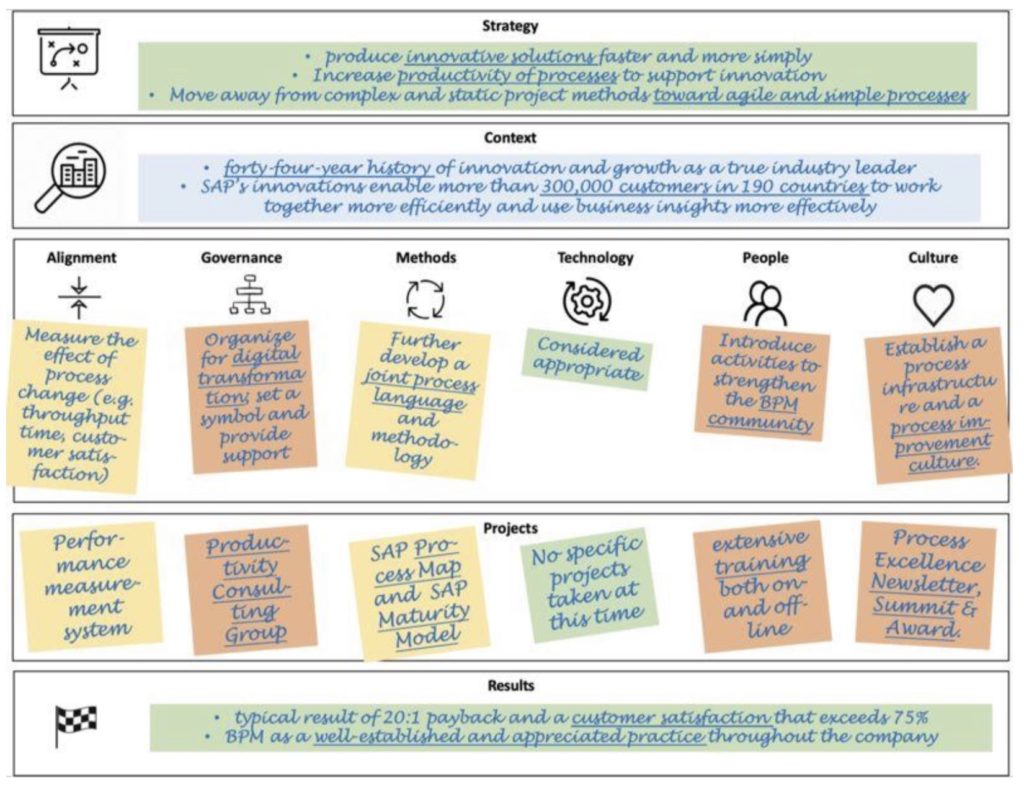

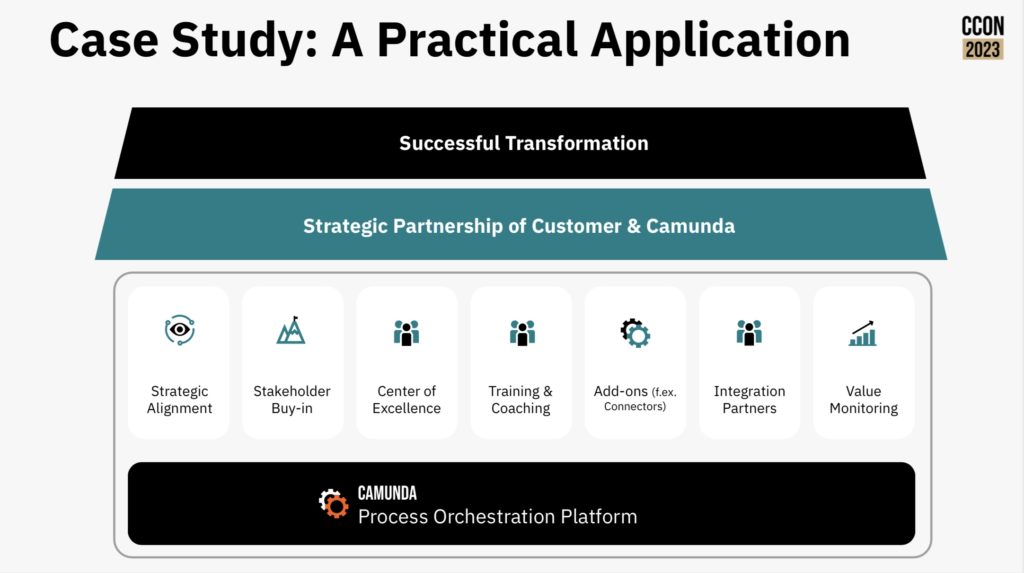

Camunda has more than 500 customers globally now, and has amassed over 5000 use cases for how those organizations are using Camunda’s software. This has allowed them to develop a process orchestration maturity model: from single projects, to broader initiatives, to distributed adoption, to a strategic scaled adoption of process orchestration. Although obviously Jakob sees the Camunda Process Orchestration Platform as a foundational platform, he looked at a number of other non-technical components such as stakeholder buy-in, plus technical add-ons and integration partners. I like that he started with strategic alignment and ended with value monitoring wrapping back to the alignment; this type of alignment between strategic goals and operational metrics is something that I strongly believe in and have written about quite a bit.

Since we’re in New York, his process orchestration in action part was focused on financial services, although with lessons for many other industries. I work a lot with my own financial services clients, and the challenges listed are very familiar. He walked through case studies of Desjardins (legacy BPMS replacement), Truist (merging systems from two merged banks), National Bank of Canada (automation CoE to radically reduce project development time), and NatWest (CoE to aid self-service projects).

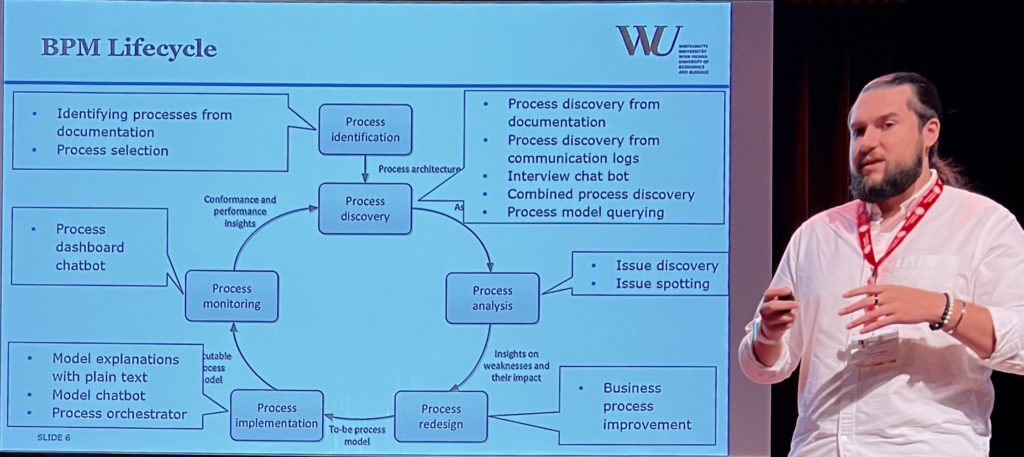

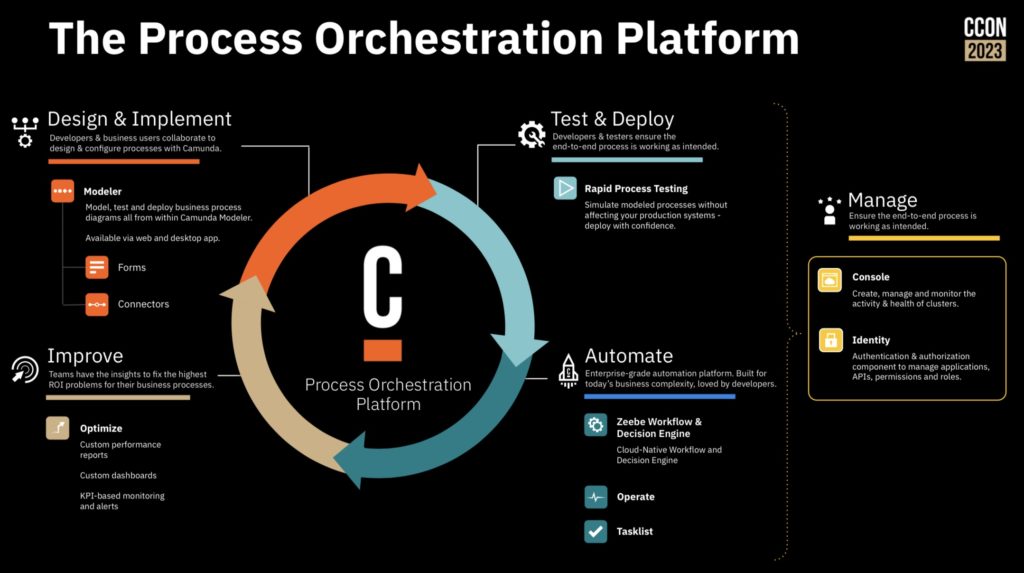

He moved on to talk about the innovation that Camunda is introducing through their technology. They now address more of the BPM lifecycle than they started out with — which was purely as a developer tool — and now provide more tools for business and IT to collaborate on process improvement/automation projects. They are also addressing the accelerating of solutions through some low-code aspects; this was a necessary move for them in the face of the current market. Their challenge will be keeping the low code tooling from getting in the way of the developers, and keeping the technical details from getting in the way of the business people.

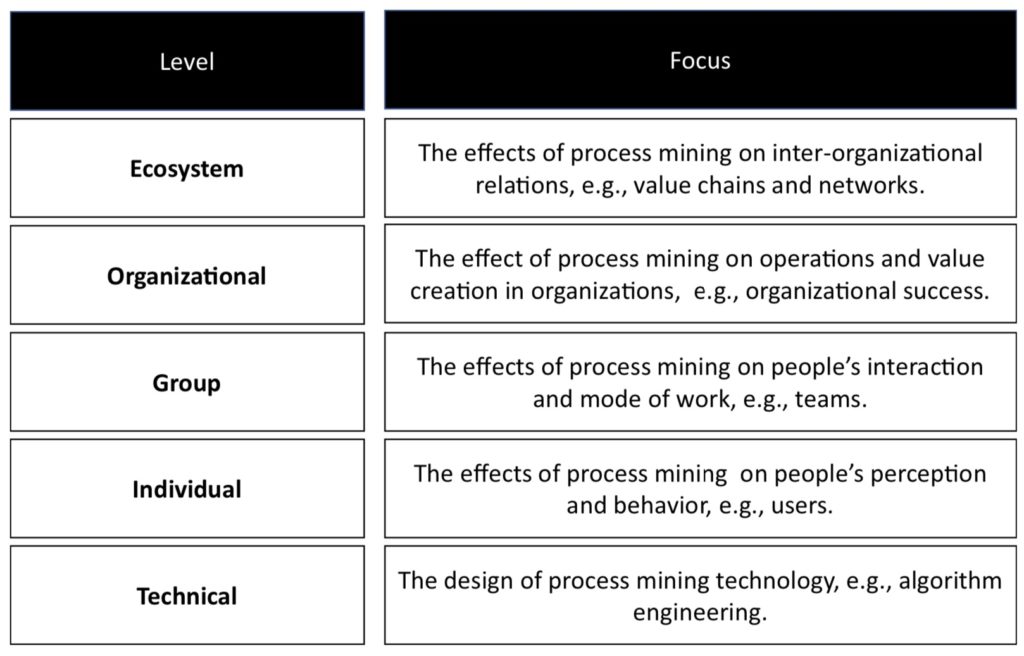

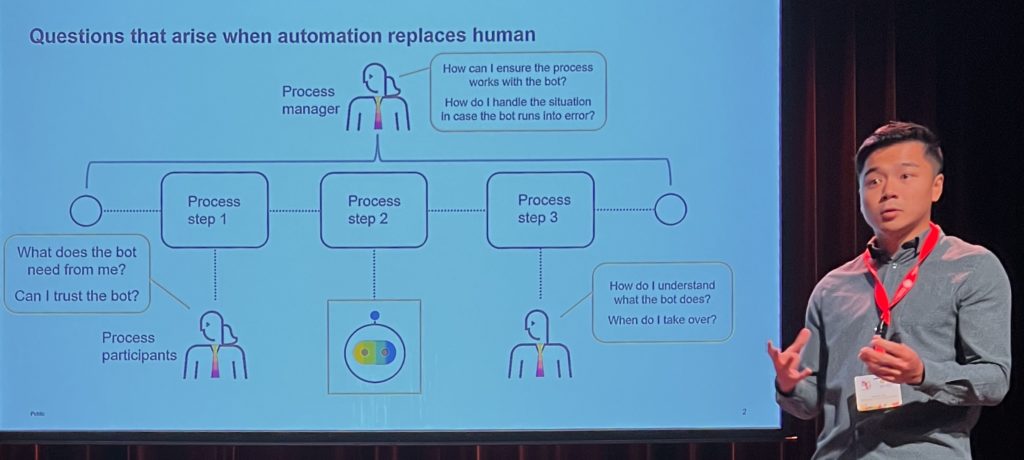

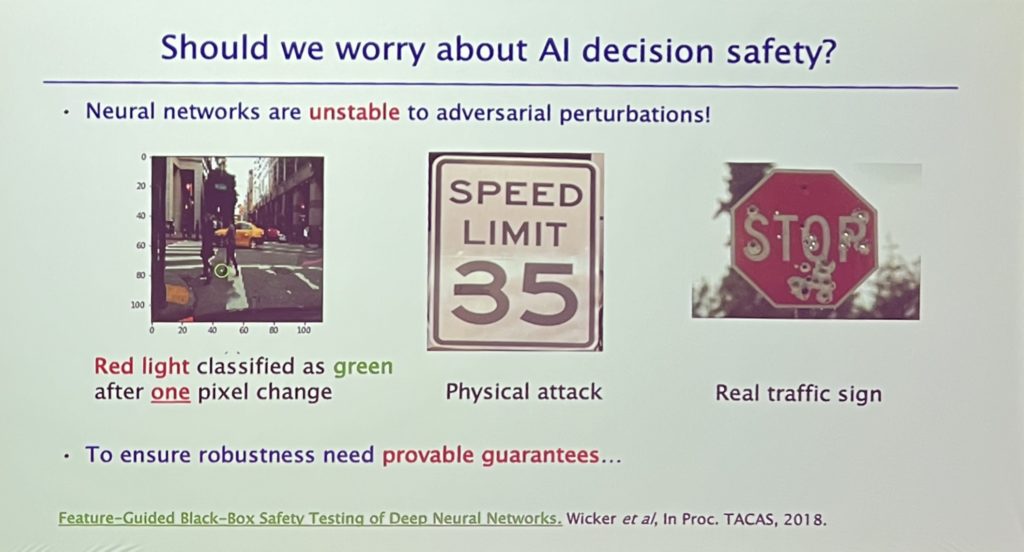

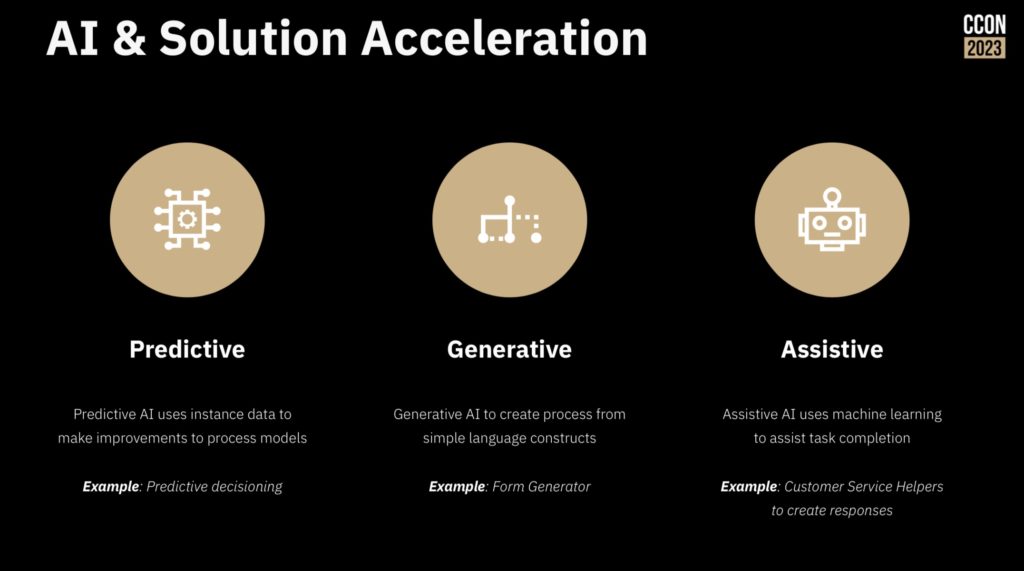

No technical conference today is complete without at least one slide on AI, and Jakob did not disappoint. He walked through how they see AI as it applies to process orchestration: predictive AI (e.g., process mining and decisioning), generative AI (e.g., form generator from simple language), and assistive AI (e.g., knowledge worker helper).

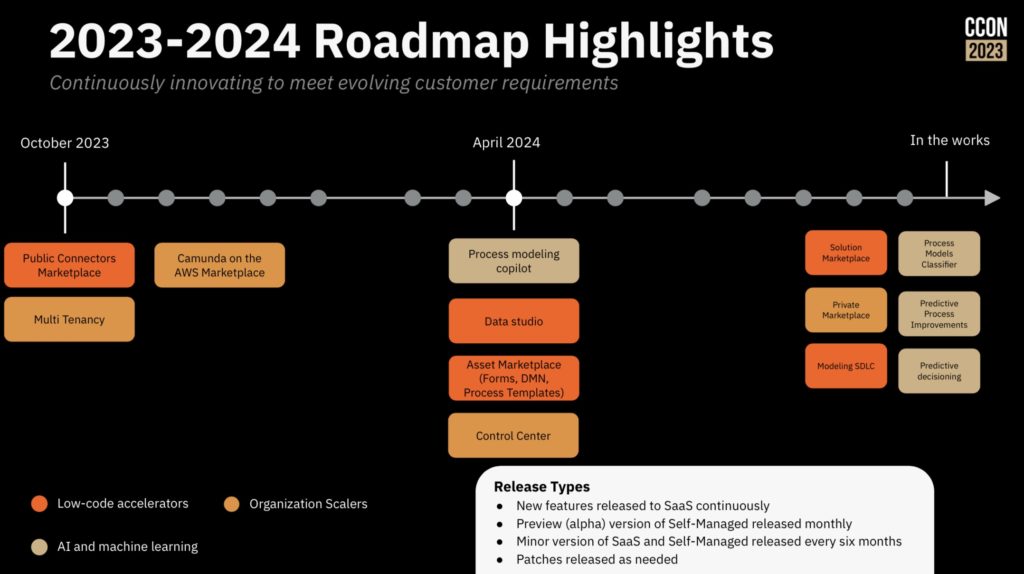

He described their connectors marketplace, which includes connectors created by them but also curated from their partners. Connectors are essential for integration, but their roadmap also includes process templates, internal marketplaces within an organization, and entire industry solutions and applications. This is an ambitious undertaking that a lot of vendors have done badly, and I’ll be very interested in seeing how this develops.

He finished up with some larger architecture issues: cloud support, security and compliance, multi-tenancy and how this allows them to support organizations both big and small. Their roadmap shows a lot of components that are targeted at broadening their reach while still supporting their long-term technical customers.