A good article by Bruce Silver on the convergence of BPM and SOA, including some speculation about what Oracle might be about to spring on the BPMS market.

Category: process

business process management

A Short History of BPM, Part 4

Continued from Part 3.

Part 4: Creating the Light, Stars, Moon and Sun

(Okay, the Genesis analogy is getting a bit old, but this really is a tale of creation.)

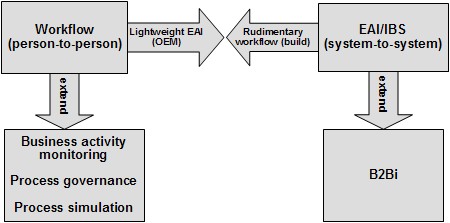

Organizations that had implemented workflow quickly realized that once the process became electronic instead of paper-driven, it wasn’t possible to monitor the process just by walking around the shop floor. Workflow monitoring and reporting were born from the need to understand where the process was — and wasn’t — working, and this was often a highly customized capability. After years of customers building their own custom reporting and monitoring tools, or using third-party analytics, the workflow products started to extend their native capabilities into this area. The early real-time monitoring grew to become a part of what we now know as business activity monitoring, or BAM. Process management and governance, both through this real-time monitoring and historical reporting and analysis, became a critical part of the process to customers, especially those implementing quality programs such as Six Sigma. The need to optimize processes pushed beyond analytics to process simulation and optimization tools.

EAI products grew in a different direction altogether. Most of the products provided some degree of reporting and analytics, and didn’t need the process governance associated with human-facing workflow. Instead, EAI vendors started to look outside the organization, and extended EAI to business-to-business integration, or B2Bi. This process collaboration allowed their customers to implement processes — still primarily system-to-system — that loosely coupled their business processes with those of their customers and other trading partners, not just flows between internal systems.

This would become one of the most significant advances for the type of BPM that we have today, allowing organizations to include both human and system participants in processes that span multiple organizations. The ROI on B2Bi can be enormous, and allows for the creation of a sort of configurable “business process firewall” as a standard process interface between an organization and its trading partners so that either can change their internal processes and data without disturbing the other.

Next: convergence and confusion.

A Short History of BPM, Part 3

Continued from Part 2.

Part 3: Creating the Firmament

In the late 1990’s, as workflow vendors saw the benefits of EAI and understood how it could replace the more heavily customized integration that was typical for workflow solutions, they began adding EAI capabilities to their workflow products. Although there were exceptions, this was typically done by the workflow vendor striking an OEM agreement with an EAI vendor to allow the EAI product to be embedded seamlessly into the workflow product.

Not surprisingly, EAI vendors saw the benefits of having some human-facing steps in the system-to-system processes, and began adding rudimentary human-facing capabilities. These functions, usually built by the EAI vendor directly rather than partnering with a workflow vendor, were fairly rudimentary since they were intended just for the repair of processes that had an exception condition that could not be handled automatically. You could say that these processes were “human interrupted” rather than “human facing”.

Although we now had systems that (theoretically) spanned the full range of the integration space, these were really just workflow systems with a bit of EAI, or EAI systems with a bit of workflow, and the vendors still sold to their strong suit.

Next: sideways diversification.

A Short History of BPM, Part 2

Continued from Part 1.

Part 2: Creating Night and Day

While workflow was getting its start in the 1980’s, enterprise application integration, or EAI, emerged independently for system-to-system integration.

A key player in the early days (and still today) was IBM with their MQ Series messaging, which became a de facto standard for system-to-system communication in many large organizations. Many other vendors entered the market, and a variety of technical architectures for message brokers emerged, but all had the same basic goal: to automate the near-real-time exchange of data between systems, typically mainframe-based transaction processing systems or server-based relational databases.

Even the simple functionality provided by early versions of EAI could reap huge benefits in two areas:

- It was no longer necessary to re-enter data in order to transfer it between systems, reducing data entry efforts and error rates.

- Information could be exchanged between systems in near-real-time, rather than relying on overnight batch updates.

These early EAI systems had no human-facing functionality, since they assumed that the applications being integrated provided all required user interface. In other words, if an error occurred sending data from system A to system B, the data or other problem would be fixed in one of those two systems, not in the EAI system.

Workflow and EAI lived very separate lives during that time, although they are now seen as two ends of the same integration spectrum. Not only were they created by two different camps of vendors (with a few not-very-succesful exceptions), and based on different technologies and standards, but they were sold to two different parts of the customer organization: workflow was typically sold to business units as a departmental solution, where as EAI was sold to IT as an infrastructure component.

Next: workflow meets EAI.

Another BPM blogger

Keith Swenson, chief architect at Fujitsu Software (and therefore of their Interstage BPM product), now has a blog. He’s involved in the WfMC and BPM standards, which I heard him speak about at the Gartner BPM Summit earlier this year.

BPM and BI

Lots of interesting news recently on BPM and BI. Last month, Lombardi and Cognos signed an OEM agreement to embed Lombardi’s Teamworks into Cognos’ analytics applications. Bruce Silver had a good post about the implications of this agreement, and the blurring lines between BPM and analytics. Then last week, IBI announced that they’ve embedded their WebFocus business intelligence into iWay‘s Process Manager (iWay is a subsidiary of IBI), further indicating this blurring of technologies.

A Short History of BPM, Part 1

Since I am fast approaching the 19th anniversary of starting my first company, which provided integration services for imaging, document management, workflow, e-commerce and eventually BPM, I have a bit of an historical perspective on the the field and often end up explaining to customers how BPM got to where it is today: sometimes as part of my Making BPM Mean Business course, and sometimes just as a standalone presentation. Although a lot of readers of this blog are BPM professionals of some sort, I’m going to reproduce this history lesson here in several parts. Click on the category BPMhistory in the sidebar to see the complete set to date.

I welcome comments from any of you other “old-timers” out there, and will incorporate relevant corrections and comments into the body of the post.

Part 1: In The Beginning

In the beginning there was workflow. To be more precise, there was person-to-person routing of scanned documents through a pre-determined process map.

As far as I know, FileNet was the first to use the term “workflow” in this context, back in the early 1980’s when they started up, although they were quickly joined in the marketplace by IBM and other product vendors. Most of these early workflow systems were document-focused, that is, the only purpose of the workflow was to move a scanned image of a paper document from one person to another so that they could perform some action on a different system, such as transaction data entry. This was a logical step after organizations started scanning their documents in order to preserve and share them: why not scan them before working on them, then pass them around electronically to try and improve efficiencies? Unfortunately, any direct integration between these other systems and the workflow processes was custom-built, expensive, and not very flexible.

From these early beginnings, workflow systems evolved fairly slowly during the 90’s into products that were much more functional and flexible, primarily in the area of better integration capabilities, more diverse server and client platforms, and some basic process modelling and process monitoring tools. In many cases, however, the workflow products were still very document-centric: the document scanning/management business was such a cash cow for many of these vendors that they didn’t show a lot of vision when it came to finding uses for workflow concepts outside of routing documents around an office. That set the stage for two things to happen:

- Third-party add-ons to popular workflow products would proliferate, to do all the things that the workflow vendors didn’t deem important.

- More nimble “pure” workflow startups (the early BPM products) would ignore the document-centric side and build highly-functional workflow products that were unable to handle an enterprise workload, but would push the envelope in terms of functionality.

Before we get to that, however, we need to talk a bit about EAI.

BPM Implementation Pitfalls

Although the AIIM E-DOC magazine site still shows the January/February issue, you can find the link to the article that I wrote for the March/April issue here (or check out the dead-tree version of the publication). In this article, I highlight three major pitfalls that can occur during BPM system implementations:

- Over-customization

- Allowing the business to design the solution

- Applying the wrong BPM tool

A couple of oddities in the online version: the entire last section is in boldface, rather than just the first header sentence (“Apply the wrong BPM tool”) in that section; and my mini-bio at the end states “Sandy Kemsley has BPM experience from the lenses vendor, user, and, currently, consultant experience.” I have no idea what that means, but enjoy the article.

EA and process modelling

I saw this post by John Wu on the myth of business process-centric enterprise definition (via Lucas Rodríguez Cervera), and I find it hard to see how anyone gets away with “defining the enterprise based on business process modeling in EA”. Business process modelling has a place in enterprise architecture, but it’s just one of many tools/techniques for creating the necessary EA artifacts. For example, if you’re a Zachman follower, you’ll find business models only in row 2 (business model/owner context), and something that could be described as a business process model really only in columns 2 (function) and 4 (people) of that row: two artifacts out of 30.

Wu proposes defining the enterprise from the aspect of mission (why), function (how), information (what), stakeholders (who), stakeholder location (where) and stakeholder demand (when) rather than the exhausted [sic] enumeration of business process modeling, which really seems just to be advocating an EA approach to defining the enterprise. And if you’re an enterprise architect, regardless of the framework that you use, you already know that business process models are just one aspect of that definition.

It’s important to understand business processes as part of understanding the enterprise, but I don’t agree with Wu’s statement that most EA projects use business process modelling as their primary understanding of the business, or that EA is just second-generation BPR.

Modelling processes without a BPMS

An article by Bruce Silver in Intelligent Enterprise discusses the recent spate of BPM vendors releasing their process modelling tools for free. He lists Savvion, Oracle and Intalio, but the trend is widening — TIBCO just announced the availability of their modeling tool, and although the press release doesn’t specify, I heard a rumour that it’s free as well (how could it not be, considering the competition?). These offerings, from companies who make their money on the BPMS engine side so can afford to give away the modelling tools, will certainly make a dent in the market share of some of the dedicated modelling tools, such as Proforma, although many of the dedicated tools provide more extensive enterprise architecture-type modelling, not just process modelling.

One significant problem with these free tools is that although the vendors assume that they will just spread to all the desktops in an organization like wildfire, most corporate IT departments lock down user desktop configurations so that you can’t install applications. Although this might seem like a bit of Big Brother, there’s a good reason for this: it’s completely impossible for a corporate IT department to support several thousand PCs if the users can just install anything that they want on them. A case in point: a few years ago, a workstation at a client of mine started freezing “randomly”, which they blamed on the BPM software that we had installed on it. After several service calls where the problem did not recur, followed by uninstalls and reinstalls, one of my engineers finally just hung around until the problem occurred. The culprit? A non-corporate-standard screen saver that showed an animated football game; the machine hung right around the first down when the cheerleaders came out. When we reverted to a standard Windows screen saver, the problem disappeared. Since then, I’ve never complained about the restrictions that corporate IT makes on standard user desktops, even though it keeps me from using Firefox at most customer sites.

What this means is that even if a vendor makes their software available for free, that doesn’t assure acceptance, because it’s not free for an organization to regression test that against their standard desktop environment(s) and all of the other applications with which it might coexist. There’s two possible solutions to this:

- Create an entirely web-based process modelling tool. (Do BPMS vendors know about Web 2.0 yet?)

- Use a modelling tool that is already on most users’ desktops, namely Microsoft Visio.

I had a chat with one of the BPMS vendors recently about the first option, and he asked if I felt that web-based was the way to go (I love it when BPMS vendors ask me my opinion on product direction 🙂 ). My reply:

I like web-based since it lowers the barrier to use… many people of the type that I see in my customers who are doing process modelling are doing so at their office location and could be doing it much more easily if they don’t have to get permission from their IT department to install something on their PC, but use a purely web-based tool.

We also discussed how an installed version was necessary for people who aren’t always connected, but most real process modellers aren’t doing it from 35,000 feet or at a trade show, they’re doing it from their desk with a high-speed corporate internet connection. Yes, you have to have something for the road warriors and your sales people, but ultimately you’ll be most successful if you build what’s best for the target audience.

Which brings me to the second solution: Visio. Last year, Bruce Silver had a couple of articles on using Visio for process modelling, referencing the itp-commerce product. I just had a demo of a competing product, Byzio from Zynium (which sounds like a fictional space alien and his planet, sort of like Mork from Ork), another Visio add-on that allows for more robust process modelling in that ubiquitous tool. Yes, you still need to install the add-on, but chances are that a corporate IT department will find it much easier to approve a Visio add-on for installation than a full application.

Basically, Byzio allows you to draw a process model in Visio, then export it to XPDL for import into a BPMS’ process modelling tool. [In case you’re not up on XPDL, it’s an XML file format used to store BPMN; BPMN is the graphic modelling notation.] You can use a BPMN stencil in Visio so that you’re using the standard BPMN shapes, but the real power of Byzio is in the ability to map from any shape to a BPMN/XPDL construct, so if you already have a corporate standard for what shapes to use in a process model, you don’t have to change that, you just have to set up the mapping. The really cool thing is that Byzio has the ability to use the text within a shape to assist in the mapping, for example, detecting the words “and” or “or” in a decision shape and choosing the correct decision type. The mapping setup, which includes a regular expression parser, is not something that you’ll want every user to be playing around with, but as long as everyone in a department is using some standard notation, you should be able to set up the mapping once and replicate it around.

Although XPDL is supposed to be a standard, every BPMS vendor has their own flavour of XPDL, so the Byzio installation has to be specific to the target BPMS: the version that was demonstrated for me was for Fujitsu Interstage, but they also list Appian and DST on their website and I know that there are others in the works. In the case of Interstage, after the XPDL file is exported from Visio using the Byzio add-on, it’s opened in the Interstage process designer, where it can be further enhanced with engine-specific parameters. Byzio also plans to support round-tripping, where the XPDL can be exported back from the BPMS process designer for import into Visio for rework — I think that there’s some serious challenges in making this happen, but it’s doable. Not as integrated as using the BPMS’ process designer directly, but it has the huge advantage of using software that’s already installed on every business analysts’ desktop.

I’m still torn on the best solution in the long run. I feel strongly that there’s a place for BPMS vendors to create fully web-based versions of their process modelling tools intended for use by business users: namely, versions of the tools that don’t include all the yucky technical details, but provide a business view of the process models as they exist in the BPMS — no importing/exporting required. However, Visio is used for so much more than just what’s going to be automated in a BPMS that it will retain its dominance in process modelling by business users for the foreseeable future. That being said, I’ll give the edge to Visio paired with add-ons such as Byzio or itp-commerce.