Martin Harris from Platform Computing presented what they’ve learned by implementing cloud computing within large enterprises; he doesn’t see cloud as new technology, but an evolution of what we’re already doing. I would tend to agree: the innovations are in the business models and impacts, not the technology itself.

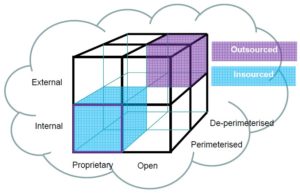

He points out that large enterprises are starting with “private clouds” (i.e., on-premise cloud – is it really cloud if you own/host the servers, even if someone else manages it? or if you have exclusive use of the servers hosted elsewhere?), but that attitudes to public/shared cloud platforms are opening up since there are significant benefits when you start to look at sharing at least some infrastructure components. Consider, for example, development managers within a large organization being able to provision a virtual server on Amazon for a developer in a matter of minutes for less than the cost of a cappuccino per day, rather than going through a 6-8 week approval and purchasing process to get a physical server: each developer and test group could have their own virtual server for a fraction of the cost, time and hassle of an on-premise server, paid for only during the period in which it is required.

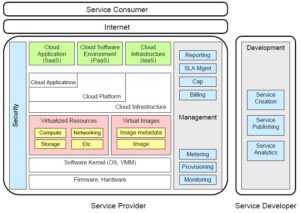

Typically, enterprise servers (and other resources) are greatly under-utilized: they’re sized to be greater than the maximum expected load even if that load occurs rarely, and often IT departments are reluctant to combine applications on a server since they’re not sure of any interaction byproducts. Virtualization solves the latter problem, but making utilization more efficient is still a key cost issue. To make this work, whether in a private or public cloud, there needs to be some smart and automated resource allocation going on, driven by policies, application performance characteristics, plus current and expected load.

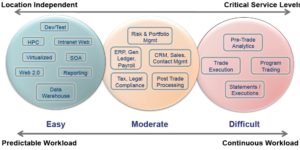

You don’t need to move everything in your company into the cloud; for example, you can have development teams use cloud-based virtual servers while keeping production servers on premise, or replace Exchange servers with Google Apps while keeping your financial applications in-house. There are three key factors for determining an application’s suitability to the cloud:

- Location – sensitivity to where the application runs

- Workload – predictability and continuity of application load

- Service level – severity and priority of service level agreements

Interestingly, he puts email gateways in the “not viable for cloud computing” category, but stated that this was specific to the Canadian financial services industry in which he works; I’m not sure that I agree with this, since there are highly secure outsourced email services available, although I also work primarily with Canadian financial services and find that they can be overly cautious sometimes.

He finished up with some case studies for cloud computing within enterprises: R&D at SAS, enterprise corporate cloud at JPMC, grid to cloud computing at Citi, and public cloud usage at Alatum telecom. There’s an obvious bias towards private cloud since that’s what his company provides (to the tune of 5M managed CPUs), but some good points here regardless of your cloud platform.