AIIM Toronto runs some great morning seminars every month or so, and today the guest is Else Khoury of Seshat Information Consulting to talk about privacy regulations. In the face of recent privacy gaffes from the Facebook fiasco (the breach that wasn’t a breach) to Alphabet Labs not thinking about where public data that they collect in Toronto will be stored (hello, data sovereignty), and with the upcoming GDPR regulations, privacy is hot right now. Khoury, who brightened our day by telling us that her company is named after the Egyptian goddess of recordkeeping, covered both Canadian and EU privacy frameworks.

AIIM Toronto runs some great morning seminars every month or so, and today the guest is Else Khoury of Seshat Information Consulting to talk about privacy regulations. In the face of recent privacy gaffes from the Facebook fiasco (the breach that wasn’t a breach) to Alphabet Labs not thinking about where public data that they collect in Toronto will be stored (hello, data sovereignty), and with the upcoming GDPR regulations, privacy is hot right now. Khoury, who brightened our day by telling us that her company is named after the Egyptian goddess of recordkeeping, covered both Canadian and EU privacy frameworks.

In Canada, we’ve had the Privacy Act since 1983, which governs federal government offices and how they handle data about employees and citizens, including Freedom of Information. PIPEDA (Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act) came in 2000, setting rules for how private organizations handle personal information. As technology evolved, the Digital Privacy Act of 2015 made major amendments to PIPEDA regarding mandatory breach reporting and recordkeeping. Khoury briefly covered FIPPA (Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act) and MFIPPA, which apply the same sort of regulations as the Privacy Act but for provincial and municipal governments. PHIPA (Personal Health Information Protection Act) protects our health-related information across all types of health care providers, and was updated quite recently to state that “use” includes viewing information after a few cases of nosy health care workers who looked up records on people who they shouldn’t have. There is (or soon will be) mandatory reporting of PHIPA breaches in most provinces, including reporting to the regulatory colleges for different types of health care workers. There is also a privacy framework for electronic health records (EHR) under new revisions to PHIPA.

There are analogous privacy regulations in many other countries; for example, the US HIPAA serves the same purpose as our PHIPA, while GDPR is a broader regulation that will cover data across all organizations rather than our division by private and public sector.

There was a good discussion on security versus privacy: security is often focused on keeping external parties out, whereas privacy has to do with how people handle data inside an organization, although these are often intertwined issues. Of course, it’s possible to have a privacy breach (e.g., inappropriate internal access) without a security breach and vice versa. Khoury pointed out that a lot of privacy regulations have to do with processes; in my experience, compliance regulations in general are very process-driven, and the best way to both avoid privacy breaches as well as prove that you have safeguards in place is to implement and audit processes around how data is handled.

She moved on to GDPR, which comes into effect in the EU in May of this year; GDPR covers all personal data of EU residents, since often the combination of data from multiple sources can be used to identify individuals even when a specific identifier (such as name) is not present. As with the 10 privacy principles in Canadian privacy regulations, GDPR has a set of key principles, and uses the concept of Privacy by Design that was co-developed by Ontario’s privacy commissioner. GDPR has specific rules around data retention, specifically not keeping data longer than is required, then securely destroying it. This led to a really interesting discussion of how companies that provide recommendations handle retention of historical data about your interactions with them, such as Netflix or Amazon: will we need to explicitly give them permission to keep information about our past purchases/consumption in order for them to give us better recommendations? GDPR will forever shift data permissions from opt-out to opt-in for Europeans, although that has been creeping up on us for a while.

One of the most talked-about GDPR principles is the right to be forgotten — Google has already received millions of take-down requests under that part of the regulation — although it doesn’t apply to most health care data since that is required to provide proper medical care to an individual. They also have breach reporting regulations similar to Canada’s PIPEDA requirements, and pretty significant penalties if a breach occurs or an organizations can be proven to be non-compliant.

She finished up with a discussion of how privacy regulation changes are likely to impact organizations, and how to operationalize privacy regulations, which depends on the type of data you handled (PI versus PHI), how you interact with it (processing versus controlling), and if you have a privacy management program in place. You’ll need to assess your holdings — what data you collect, how it’s used, who has access, how long it is retained, how it to secured and destroyed — and develop a privacy management team that includes involvement of senior management and every department, not just a data privacy officer (DPO). You’ll need to develop a privacy management program that includes a breach response process, ensure that everyone is trained in privacy management, then audit and adapt it over time. If you’re subject to the GDPR, then you’ll also need processes for expunging data from your systems due to “right to be forgotten” requests in a timely fashion.

You’ll also need to develop a framework for data protection impact assessments (DPIA, aka privacy impact assessments or PIA) which is a proactive risk assessment for new programs or systems that use personal data: interestingly, the first part of this is often mapping the information flow processes that cover collection, storage and access. Performing DPIA/PIA is part of what Khoury’s company does for organizations, and she had a good checklist of the steps involved, as well as pointing out that they should be a regular part of your privacy management program, not something that’s just done at the end as an audit step.

As always, great content at the AIIM Toronto morning seminars, and I look forward to the next one.

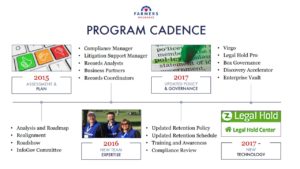

In the last Thursday breakout of AIIM 2018, I attended a session on initiatives within the compliance department at Farmers Insurance to modernize their records management, presented by Rafael Moscatel. Their technology includes IGS’ Virgo to manage retention schedules, Legal Hold Pro for legal holds and custodian compliance, and Box for content governance. They started in 2015 with an assessment and plan, then built a new team with the appropriate expertise going forward, then updated their policy and governance, and finally brought in the three new key technology components in 2017. For an insurance company, that’s pretty fast.

In the last Thursday breakout of AIIM 2018, I attended a session on initiatives within the compliance department at Farmers Insurance to modernize their records management, presented by Rafael Moscatel. Their technology includes IGS’ Virgo to manage retention schedules, Legal Hold Pro for legal holds and custodian compliance, and Box for content governance. They started in 2015 with an assessment and plan, then built a new team with the appropriate expertise going forward, then updated their policy and governance, and finally brought in the three new key technology components in 2017. For an insurance company, that’s pretty fast. Their retention policy is based on 12 big buckets, which are primarily aligned with business functions, making it easy for employees to understand what they are from a real-world standpoint. Legal Hold Pro replaced an old customized SharePoint system, and works together with Box Governance for e-discovery. He went through a lot of the details of how the technologies work together and what they’re doing with them, but the key takeaway for me is that an insurance company — what I know through a lot of experience to be an

Their retention policy is based on 12 big buckets, which are primarily aligned with business functions, making it easy for employees to understand what they are from a real-world standpoint. Legal Hold Pro replaced an old customized SharePoint system, and works together with Box Governance for e-discovery. He went through a lot of the details of how the technologies work together and what they’re doing with them, but the key takeaway for me is that an insurance company — what I know through a lot of experience to be an