Fujitsu is releasing version 10 of their Interstage BPM, and I had a chance for an in-depth demo a few weeks ago in advance of today’s announcement. On the design side, their new version of Studio now allows business analysts and IT to work together, and includes forms development. In terms of end-user functionality, there’s some improvements to workflow to enable collaboration, and new dashboard functionality. Most exciting (I think) is full support for multi-tenanting in order to allow for shared services and SaaS.

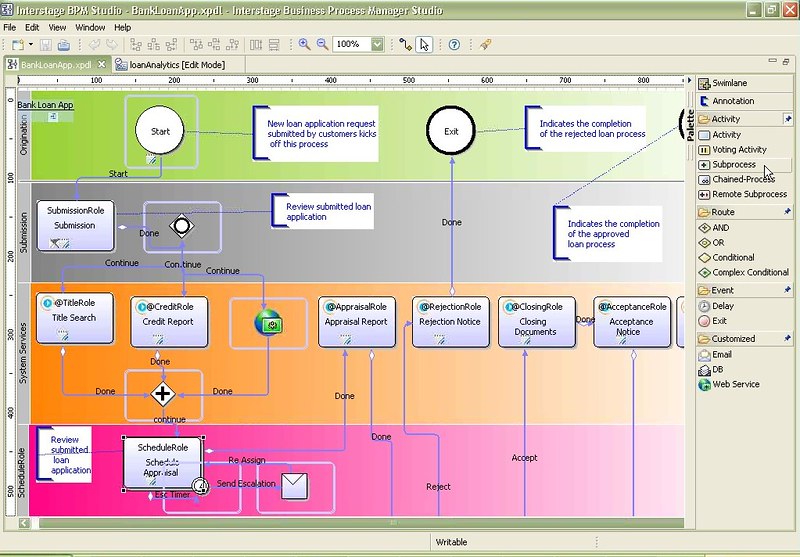

Key new features in Studio V10:

- Full application development rather than just process modeling in Studio: create AJAX forms (rich user interfaces) to be attached at a point in the process, BAM designer, and simulation.

- BPMN compliance, including annotation capabilities for inline documentation, plus some extensions to the notation in order to show things such as the presence of a form attached at a step. I explicitly asked which BPMN objects are not supported, and got a sort of fuzzy answer, that is, that they support all the BPMN objects required for their modeling paradigm. There are two other BPMN views besides the baseline standard: one showing the role at each step — which assumes that you’re not using swimlanes for roles — and one version with coloured swimlanes.

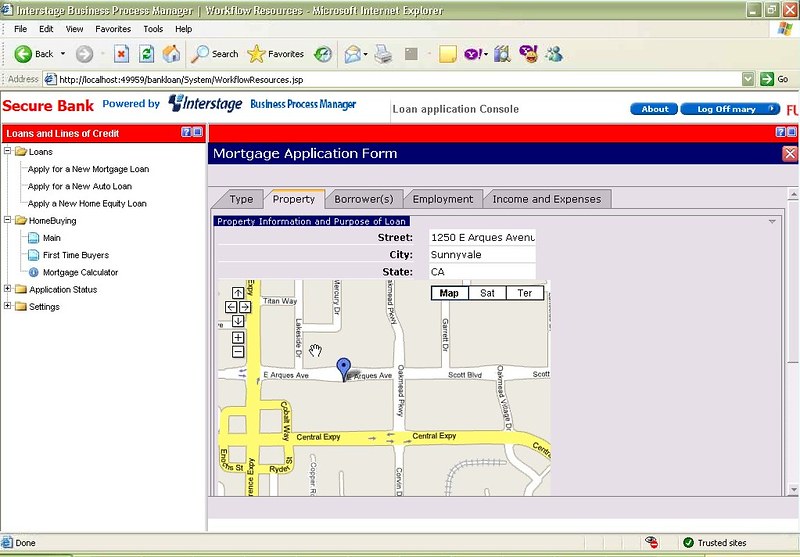

- WYSIWYG forms designer allows widgets to be dragged and dropped from the palette, including complex widgets such as Google maps, breadcrumbs, and file uploaders: this is almost a mashup builder rather than just basic forms. There’s also BPM-specific widgets to allow you to easily add controls both for a work item’s metadata as well as functionality. You can add validation rules to fields.

- Once a form is created in the forms designer, it can be dragged onto a workflow step to assign the form to that step.

- The analytics designer is a separate perspective in Studio that allows creation of alert rules that will fire based on conditions in a workflow, then take an action: open an alert window to a user, generate a chart, or trigger another action. Charts are defined as independent objects, then a presentation dashboard can be built including a selection of charts, including role-based security.

- There’s a built-in decision tables functionality that separates rules from processes, so that process-related rules can be changed independently and will affect work in progress. I still don’t like this approach as much as an external rules system, but this is much better than using just a simple expression engine with “rules” embedded at points in the process. Interstage can, of course, also support third-party rules engines plugged in for more comprehensive rules capabilities.

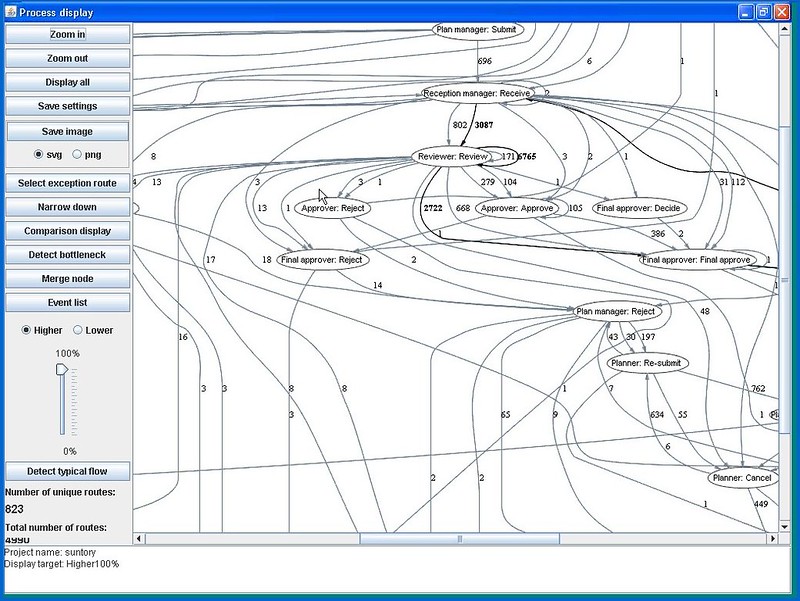

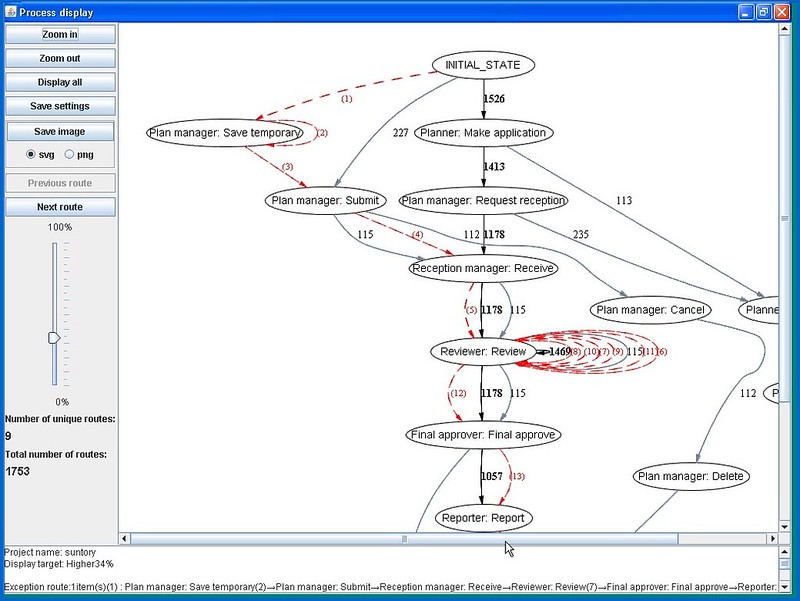

- Simulation based on predefined values or historical values, plus the specification of resource costs. No tools for automatically identifying areas requiring improvement, although they hinted that this was in the works.

End-user interface updates:

- The user interface is now created primarily using the forms created in the new form designer. In the sample that I saw in the demo, there was a multi-page form to represent a process instance, where the first page was text fields, and second page was a Google Map with the property location related to the process instance tagged on it: a nice example of the actual use of a Google Maps mashup in a business application. The form provides access to the instance metadata and any attachments, then allows the user to fill out additional form data and complete the task.

- Depending on the user’s privileges, there’s an administrator’s view of the process, and a browser-based (Flash) process designer to allow either complete process modeling or (more likely) to modify a process in flight. Changes made to a single process in this environment can be migrated to all process in flight.

Interstage BPM enforces stringent J2EE compliance, such that any process model, rule, etc. built automatically become a web service that can be exposed.

Application partitioning capabilities to allow for SaaS: support for multiple applications on a single BPM instance with fully partitioned data, security and administration so that it appears as a private BPM instance, and utilization can be tracked by application. This is great for large enterprises that want to run virtual independent BPM environments for different divisions or applications, as well as companies that might want to use Interstage as a foundation for a SaaS BPM offering.