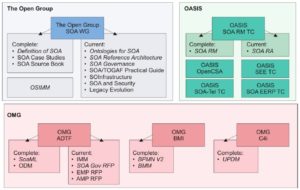

It’s impossible for me to pass up a standards discussion (how sad is that?), so I switched from the business analysis stream to the SOA stream for Heather Kreger’s discussion of SOA standards at an architectural level. OASIS, the Open Group and OMG got together to talk about some of the overlapping standards impacting this: they branded the process as “SOA harmonization” and even wrote a paper about it, Navigating the SOA Open Standards Landscape Around Architecture (direct PDF link).

It’s impossible for me to pass up a standards discussion (how sad is that?), so I switched from the business analysis stream to the SOA stream for Heather Kreger’s discussion of SOA standards at an architectural level. OASIS, the Open Group and OMG got together to talk about some of the overlapping standards impacting this: they branded the process as “SOA harmonization” and even wrote a paper about it, Navigating the SOA Open Standards Landscape Around Architecture (direct PDF link).

As Kreger points out, there are differences between the different groups’ standards, but they’re not fatal. For example, both the Open Group and OASIS have SOA reference architectures; the Open Group one is more about implementation, but there’s nothing that’s completely contradictory about them. Similarly, there are SOA governance standards from both the Open Group and OASIS

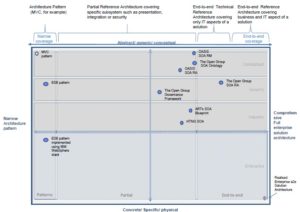

They created a continuum of reference architectures, from the most abstract conceptual SOA reference architectures through generic reference architectures to SOA solution architectures.

They created a continuum of reference architectures, from the most abstract conceptual SOA reference architectures through generic reference architectures to SOA solution architectures.

The biggest difference in the standards is that of viewpoint: the standards are written based on what the author organizations are trying to do with them, but contain a lot of common concepts. For example, the Open Group tends to focus on how you build something within your own organization, whereas OASIS looks more at cross-organization orchestration. In some cases, specifications can be complementary (not complimentary as stated in the presentation 🙂 ), as we see with SoaML being used with any of the reference architectures.

Good summary, and I’ll take time to review the paper later.