For the last session of the day, I attended Carol Rozwell’s presentation on social network analysis and the impact of understanding network processes. I’ll be doing a presentation at Business Rules Forum next month on social networking and BPM, so this is especially interesting even though I’ll be covering a lot of other information besides social graphs.

She started with the (by now, I hope obvious) statement that what you don’t know about your social network can, in fact, hurt you: there are a lot of stories around about how companies have and have not made good use of their social network, and the consequences of those activities.

She posited that while business process analysis tells us about the sequence of steps, what can be eliminated and where automation can help, social network analysis tells us about the intricacies of working relationships, the complexity and variability of roles, the critical people and untapped resources, and operational effectiveness. Many of us are working very differently than we were several years ago, but this isn’t just about “digital natives” entering the workforce, it’s about the changing work environment and resources available to all of us. We’re all more connected (although many Blackberry slaves don’t necessarily see this as an advantage), more visual in terms of graphical representations and multimedia, more interactively involved in content creation, and we do more multitasking in an increasingly dynamic environment. The line between work and personal life blurs, and although some people decry this, I like it: I can go to many places in the world, meet up with someone who I met through business, and enjoy some leisure time together. I have business contacts on Facebook in additional to personal friends, and I know that many business contacts read my personal blog (especially the recent foodie posts) as well as my business blog. I don’t really have a lot to hide, so don’t have problem with that level of transparency; I’m also not afraid to turn off my phone and stop checking my email if I want to get away from it all.

Your employees are already using social media, whether you allow it within your firewall or not, so you might as well suck it up and educate them on what they can and can’t say about your company on Twitter. If you’re on the employee side, then you need to embrace the fact that you’re connected, and stop publishing those embarrassing photos of yourself on Facebook even if you’re not directly connected to your boss.

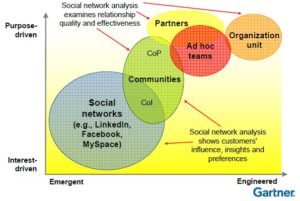

She showed a chart of social networks, with the horizontal axis ranging from emergent to engineered, and the vertical axis from interest-driven to purpose-driven. I think that she’s missing a few things here: for example, open source communities are emergent and purpose-driven, that is, at the top left of the graph, although all of her examples range roughly along the diagonal from bottom left to top right.

She showed a chart of social networks, with the horizontal axis ranging from emergent to engineered, and the vertical axis from interest-driven to purpose-driven. I think that she’s missing a few things here: for example, open source communities are emergent and purpose-driven, that is, at the top left of the graph, although all of her examples range roughly along the diagonal from bottom left to top right.

There are a lot of reasons for analyzing social networks, such as predicting trends and identifying new potential sources of resources, and a few different techniques for doing this:

- Organizational network analysis (ONA), which examines the connections amongst people in groups

- Value network analysis (VNA), which examines the relationships used to create economic value

- Influence analysis, a type of cluster analysis that pinpoints people, associations and trends

Rozwell showed an interesting example of a company’s organizational chart, then the same players represented in an ONA. Although it’s not clear exactly what the social network is based on – presumably some sort of interpersonal interaction – it highlights issues within the company in that some people have no direct relation to their direct reports, and one person who was low in the organizational chart was a key linkage between different departments and people.

She showed an example of VNA, where the linkages between a retailer, distributor, manufacturer and contract manufacturer where shown: orders, movements of goods, and payments. This allows the exchanges of value, whether tangible or intangible, to be highlighted and analyzed.

Her influence analysis example discussed the people who monitor social media – either within a company or their PR agency – to analyze the contributors, determine which are relevant and credible, and use that to drive engagement with the social media contributors. I get a few emails per day from people who start with “I read your blog and think that you should talk to my customer about their new BPM widget”, so I know that there are a lot of these around.

There are some basic features that you look for when doing network analysis: central connectors (those people in the middle of a cluster), peripheral players (connected to only one or two others), and brokers (people who form the connection between two clusters).

There are some pretty significant differences between ONA, VNA and business process analysis, although there are some clear linkages: VNA could have a direct impact on understanding the business process flows, while ONA could help to inform the roles and responsibilities. She discussed a case study of a company that did a business process analysis and an ONA, and used the ONA on the redesigned process in order to redesign roles to reduce variability, identify roles most impacted by automation, and expose critical vendor relationships.

Determining how to measure a social network can be a challenge: one telecom company used records of voice calls, SMS and other person-to-person communications in order to develop marketing campaigns and pricing strategies. That sounds like a complete invasion of privacy to me, but we’ve come to expect that from our telecom providers.

The example of using social networks to find potential resources is something that a lot of large professional services firms are testing out: she showed an example that looked vaguely familiar where employees indicated their expertise and interests, and other employees could look for others with specific sets of skills. I know that IBM does some of this with their internal Beehive system, and I saw a presentation on this at the last Enterprise 2.0 conference.

There are also a lot of examples of how companies use social networks to engage their customers, and a “community manager” position has been created at many organizations to help manage those relationships. There are a lot of ways to do this poorly – such as blasting advertising to your community – but plenty of ways to make it work for you. Once things get rolling in such a public social network, the same sort of social network analysis techniques can be applied in order to find the key people in your social network, even if they don’t work for you, and even if they primarily take an observer role.

Tons of interesting stuff here, and I have a lot of ideas of how this impacts BPM – but you’ll have to come to Business Rules Forum to hear about that.