Continued from Part 3.

Part 4: Creating the Light, Stars, Moon and Sun

(Okay, the Genesis analogy is getting a bit old, but this really is a tale of creation.)

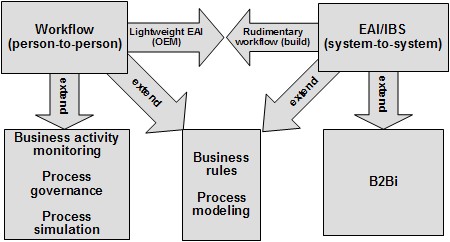

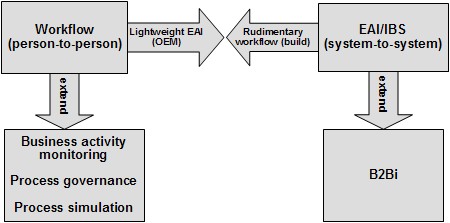

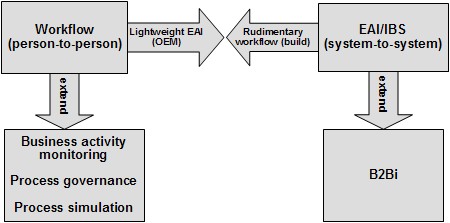

Organizations that had implemented workflow quickly realized that once the process became electronic instead of paper-driven, it wasn’t possible to monitor the process just by walking around the shop floor. Workflow monitoring and reporting were born from the need to understand where the process was — and wasn’t — working, and this was often a highly customized capability. After years of customers building their own custom reporting and monitoring tools, or using third-party analytics, the workflow products started to extend their native capabilities into this area. The early real-time monitoring grew to become a part of what we now know as business activity monitoring, or BAM. Process management and governance, both through this real-time monitoring and historical reporting and analysis, became a critical part of the process to customers, especially those implementing quality programs such as Six Sigma. The need to optimize processes pushed beyond analytics to process simulation and optimization tools.

EAI products grew in a different direction altogether. Most of the products provided some degree of reporting and analytics, and didn’t need the process governance associated with human-facing workflow. Instead, EAI vendors started to look outside the organization, and extended EAI to business-to-business integration, or B2Bi. This process collaboration allowed their customers to implement processes — still primarily system-to-system — that loosely coupled their business processes with those of their customers and other trading partners, not just flows between internal systems.

This would become one of the most significant advances for the type of BPM that we have today, allowing organizations to include both human and system participants in processes that span multiple organizations. The ROI on B2Bi can be enormous, and allows for the creation of a sort of configurable “business process firewall” as a standard process interface between an organization and its trading partners so that either can change their internal processes and data without disturbing the other.

Next: convergence and confusion.